﷽

EXPLORING TAWAQQUF IN ISLAMIC THEOLOGY:

NAVIGATING BELIEF OBLIGATIONS, ADAMIC EXCEPTIONALISM, AND APPLICATION CHALLENGES

ABSTRACT

This essay rigorously examines the theological concept of tawaqquf, or non-commitment, within the framework of Islamic theology, with a specific focus on its implications for Adamic exceptionalism. By scrutinising the indiscriminate utilisation of tawaqquf, it elucidates its inappropriate application when addressing pivotal theological inquiries. Through detailed analysis of Qur’anic verses, scholarly consensus, and the doctrinal tenets upheld by Ahl al-Sunnah w’al-Jamāʿah, the essay interrogates the legitimacy of maintaining a non-committal stance concerning critical issues such as the lineage of Prophet Ādam’s ﵇ descendants. By meticulously dissecting the multifaceted dimensions of tawaqquf and delving into the intricate nuances of theological interpretation, it aims to disentangle the conflicting implications of Adamic exceptionalism within Islamic theological discourse, as ratified by orthodoxy and consensus. Moreover, the essay underscores the imperative of deeply engaging with classical scholarly texts to establish consensus positions, which may not be explicitly stated but hold authoritative sway within the theological framework of Ahl al-Sunnah w’al-Jamāʿah, while cautioning against the potential pitfalls of deviating into theological innovation when entertaining alternative perspectives grounded in rare or rejected opinions.

Shaykh Rafāqat Rashid

JKN Fatāwa Department, Bradford UK

Al Balagh Academy, Department of Sharīʿah

Attested by Shaykh Muftī Saiful Islām

JKN Fatāwā Department, Bradford, UK

March 2024, Shaʿban 1445 AH

CONTENT

INTRODUCTION

SECTION 1 – USAGE OF TAWAQQUF IN THEOLOGY

- Defining Tawaqquf in Theology

- Types of Tawaqquf in Theology

- Inappropriate Application of Tawaqquf

SECTION 2 – PRINCIPLES DETERMINING OBLIGATIONS IN BELIEF

- Interpretation of Clear, Explicit and Ambiguous Text in Creedal Matters

- Consensual Implication on Non-explicit Wording

- The Attribution of Consensus (Ijmāʿ) to Evidence

- What the Consensus Implies

- The Ruling on Opposing Consensus, (Ijmāʿ)

- The Consensus in Matters of Belief

SECTION 3 – AHL AL-SUNNAH AND ADAMIC EXCEPTIONALISM

- What is a Human

- Lineage from a Single Soul

- Were there Humans (Insān) before Prophet Ādam ﵇

- Did we originate from one lineage only, or from others as well?

SECTION 4: HUMAN UNIQUENESS RELATED TO NAFSIN WĀḤIDAH

- Nafsin Wāhidah relating to the Critical Component of Insān

- Was the Covenant with Soul and Body Together?

SECTION 5: APPLICATION OF TAWAQQUF TO NAFSIN WĀḤIDAH

- Problems with Application of Tawaqquf

- Possibility of Interbreeding between Human and other Species

SECTION 6: PLAUSIBLE EXPLANATION FOR EMPIRICAL FINDINGS RELATED TO EVOLUTION

- Substance from which Ādam was Created.

- Creation of Prophet Ādam and its Scientific Implications

CONCLUSION

INTRODUCTION

It is asserted that in instances where definitive theological positions remain uncontradicted, and there exists no conclusive proof to affirm or refute the matter, adherence to a non-committal stance (tawaqquf) becomes imperative. This approach stems from the acknowledgement that definitive belief or rejection based on scriptural evidence is untenable under such circumstances. Consequently, proponents argue for the necessity of maintaining a stance of non-commitment towards both Adamic exceptionalism and Human exceptionalism. This non-committal position inadvertently leads to an absence of a conclusive Islamic stance on pivotal questions, such as whether biological humans underwent an evolutionary process or whether Prophet Ādam's descendants could have interbred with other hominins, potentially resulting in humans being a product of this biological evolutionary process. This situation parallels the non-committal stance often adopted within Islamic discourse concerning topics like the existence of dinosaurs, thus creating space for various theories and interpretations to coexist.[1]

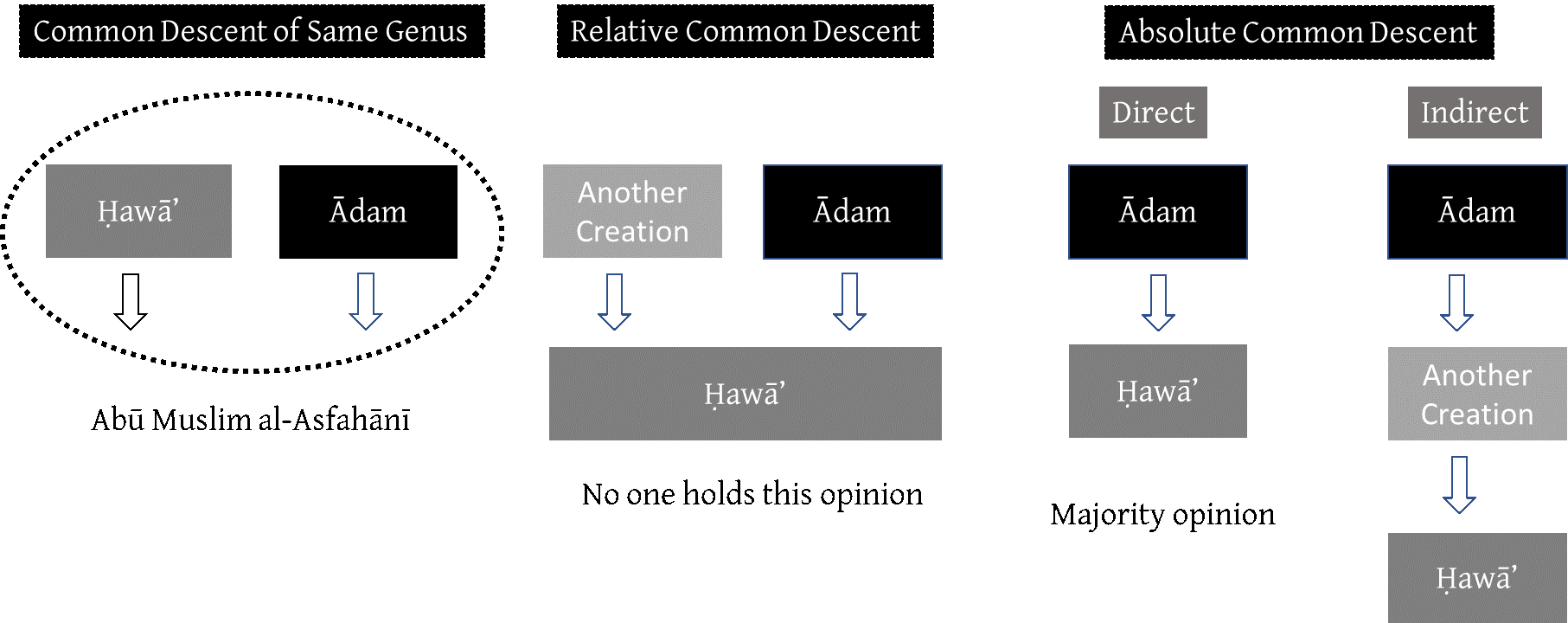

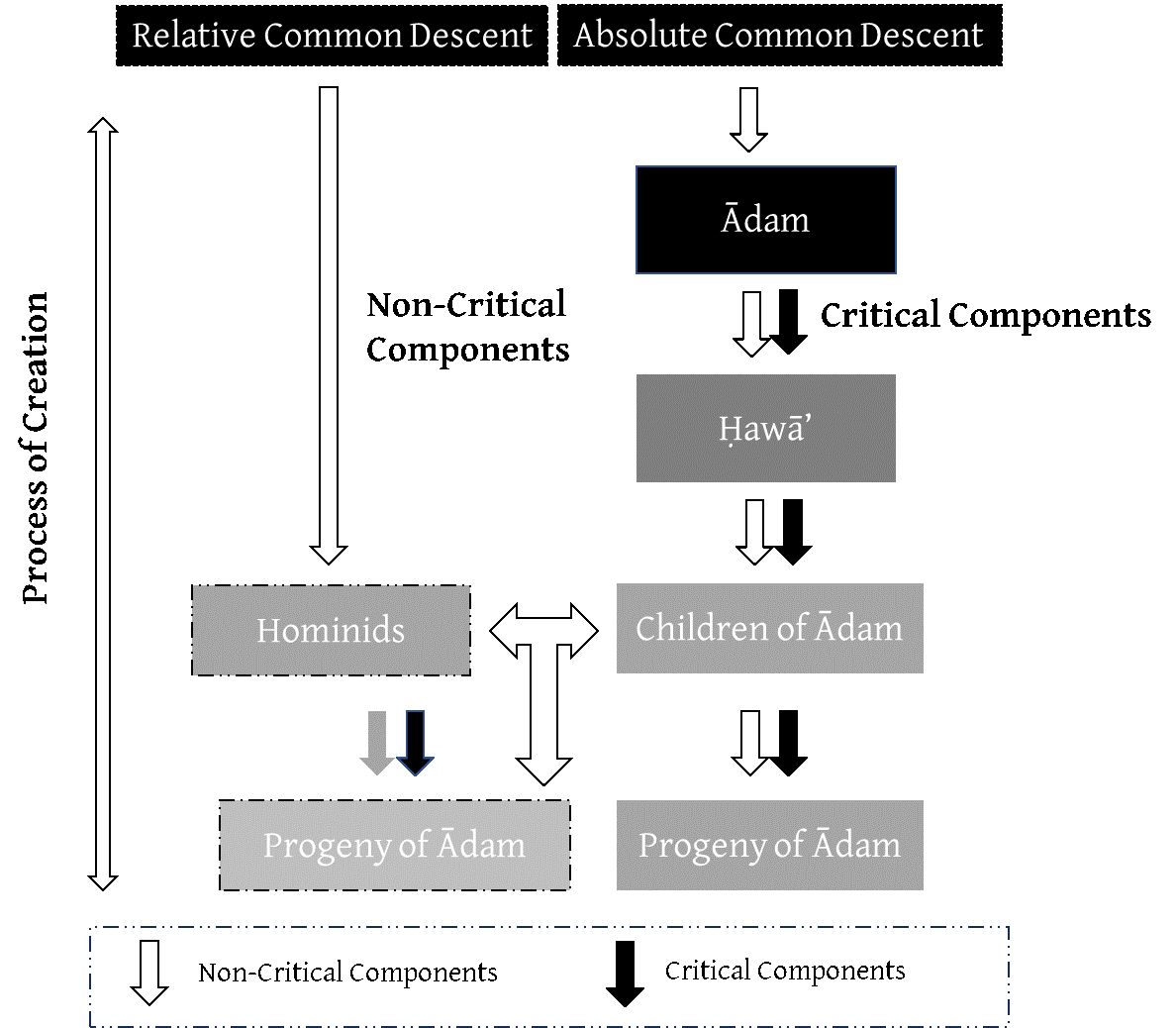

This perspective oversimplifies the systematic application of tawaqquf (the position of non-commitment) in Islamic theology, neglecting to fully address the demands inherent to such a stance. This essay aims to demonstrate the inadequacy of applying tawaqquf to the issue of Adamic exceptionalism. Contrary to claims suggesting the appropriateness of tawaqquf in this context, an examination of the Qur’anic verse (Q. 4:1) reveals a consensus (ijmāʿ) among the orthodox scholars of Islām regarding the exclusive lineage of all children of Ādam ﵇, as indicated by the term “nafsin wāḥidah.” This consensus precludes the possibility of lineage crossing, thereby challenging any deviation from this established understanding. Hence, it could be argued that considering an alternative perspective constitutes an innovation (bidʿa) within Islamic theological discourse.

[1] Theological tawaqquf, is claimed to be that which is an obligatory, permanent epistemological stance of declaring a matter unknowable, e.g., when the scriptures are totally silent about something. The assertion is that the diversification of Ādam's descendants in color, stature, and appearance suggests a broad range of human variation. However, the lack of explicit textual evidence about Ādam's earliest descendants prevents definitive conclusions about their classification as Homo sapiens or an earlier species. Questions regarding creatures like Homo Neanderthalis and the timing of Homo sapiens' evolution before Ādam remain unanswered, but their significance in both scientific and theological realms is limited.

In theological discourse, tawaqquf mandates an epistemological stance of declaring a matter unknowable when scriptures are silent on it. For instance, the absence of mention of dinosaurs in Islamic scripture prohibits arguing for or against their existence based on religious texts. Therefore, claims asserting Islam's denial or mandatory belief in dinosaurs are considered unwarranted and sinful, as they exceed scriptural evidence and delve into speculative territory.

(Malik, S.A. Islam and Evolution, Al-Ghazālī and the Modern Evolutionary Paradigm, Routledge, London 2021, 134; Jalajel DS, Islam and Biological Evolution – Exploring Classical Sunni Sources and Methodologies, MA thesis, University of the Western cape, 2009, 164)

[1] Theological tawaqquf, is claimed to be that which is an obligatory, permanent epistemological stance of declaring a matter unknowable, e.g., when the scriptures are totally silent about something. The assertion is that the diversification of Ādam's descendants in color, stature, and appearance suggests a broad range of human variation. However, the lack of explicit textual evidence about Ādam's earliest descendants prevents definitive conclusions about their classification as Homo sapiens or an earlier species. Questions regarding creatures like Homo Neanderthalis and the timing of Homo sapiens' evolution before Ādam remain unanswered, but their significance in both scientific and theological realms is limited.

In theological discourse, tawaqquf mandates an epistemological stance of declaring a matter unknowable when scriptures are silent on it. For instance, the absence of mention of dinosaurs in Islamic scripture prohibits arguing for or against their existence based on religious texts. Therefore, claims asserting Islam's denial or mandatory belief in dinosaurs are considered unwarranted and sinful, as they exceed scriptural evidence and delve into speculative territory.

(Malik, S.A. Islam and Evolution, Al-Ghazālī and the Modern Evolutionary Paradigm, Routledge, London 2021, 134; Jalajel DS, Islam and Biological Evolution – Exploring Classical Sunni Sources and Methodologies, MA thesis, University of the Western cape, 2009, 164)

To comprehensively address this issue, it is imperative to gain a deep understanding of the concept of tawaqquf and its theological implications. This necessitates a thorough examination of its definition, its application in theological discourse, and the various nuances that shape its usage. In the first section of this essay, we will delve into these aspects, delineating the types of tawaqquf, elucidating its parameters, assessing the permissibility of its use, and identifying common deviations that may arise in its application.

Building upon this foundational understanding, the second section will explore the principles related to the obligation of consensus within the theological framework of Ahl al-Sunnah w’al-Jamāʿah. This inquiry will delve into the intricate topic of the acceptance of meanings of words in scripture, examining both explicit and non-explicit wording to unravel the guiding principles of theological interpretation.

Subsequently, in the third section, we will investigate whether there exists a consensual position regarding the descent of humans insān from Ādam ﵇, as interpreted from the verse of “nafsin wāhidah.” This exploration will shed light on Ahl al-Sunnah w’al-Jamāʿah’s stance on the necessary components underpinning the discourse on Adamic exceptionalism. We will delve into fundamental questions such as the nature of humanity, the concept of lineage from a single soul, the possibility of humans (insān) existing before Ādam (as), and the origins of human lineage. Through this rigorous analysis, we aim to uncover the nuanced theological perspectives surrounding Adamic exceptionalism within Islamic theology.

In the fifth section, we will draw upon the principles of tawaqquf to scrutinise whether Adamic or Human exceptionalism can be reconciled within Islamic theology. Through a thorough examination of theological perspectives, we aim to elucidate the compatibility of these concepts within the framework of Islamic belief.

In the final section, section six navigates genetic evidence supporting evolution while aligning it with Islamic teachings on Prophet Ādam's creation from clay, adhering to the theological stance expounded in the essay. By delving into aḥadīth, it clarifies Ādam's unique creation without biological parents, revealing possible points of convergence between scientific discoveries and Islamic theological principles.

SECTION 1 – USAGE OF TAWAQQUF IN THEOLOGY

Defining Tawaqquf in Theology

The theological concept of “tawaqquf” presents a challenge due to the absence of a universally agreed-upon definition. Various expressions are employed to convey the theological stance of non-commitment or reservation when addressing inquiries related to definitive Islamic beliefs. This diversity in terminology often leads to confusion concerning the precise meaning and application of the non-commitment position as intended by Islamic theologians in specific cases.[1]

This confusion can result in the misapplication and misrepresentation of the theological use of tawaqquf, primarily due to the inconsistency and overlap of terms that sometimes refer to tawaqquf or unrelated issues. It is crucial to recognise that classical Muslim theologians typically share a consensus on the concept of non-commitment. They frequently employ phrases like “waqafa f’il-jawāb“[2] (non-commitment to a response) or “al-sukūt ʿanhu“[3] (silence) to convey this idea, although these terms may also have broader interpretations where they can be applied to discussions not directly related to Islam. However, it's important to differentiate tawaqquf from other concepts such as “mashkūk fīhi“[4] (there is

[1] انظر: التوقف في العقيدة: دراسة في المنهج والمسائل والأسباب عند أهل السنة, بدر بن سعيد الغامدي

[1] – شرح العقيدة الطحاوية المؤلف: صدر الدين محمد بن علاء الدين علي ابن أبي العز الحنفي الأذرعي الصالحي الدمشقي المتوفى ، تحقيق شعيب الأرنؤوط – عبد الله بن المحسن التركي، الناشر: مؤسسة الرسالة – بيروت، الطبعة العاشرة، ١٤١٧هـ – ١٩٩٧م. وما نقله شارح الطحاوية عن أبي حنيفة رحاله في والأنبياء: «فإن الإمام أبا حنيفة ه وقف في الجواب عنها على ما ذكره في مال الفتاوى، فإنه ذكر مسائل لم يقطع أبو حنيفة فيها بجواب، وعد منها :التفضيل بين الملائكة والأنبياء»(٤١١/٢)

[1] شرح أصول اعتقاد أهل السنة والجماعة المؤلف: أبو القاسم هبة الله بن الحسن بن منصور الطبري الرازي اللالكائي المتوفى (٤١٨هـ)، تحقيق : أحمد بن سعد بن حمدان الغامدي، الناشر : دار طيبة – السعودية، الطبعة الثامنة، ١٤٢٣هـ – ٢٠٠٣م. ما رواه اللالكائي عن مصعب أن مالكاً قال: «فأما الكلام في الله فالسكوت عنه » (1/ 165), شرح أصول اعتقاد أهل السنة والجماعة وفي اعتقاد الإمام أحمد الله : «ونذهب إلى حديث ابن عمر : كنا نعد وأصحابه متوافرون : أبو بكر، ثم عمر، ثم عثمان، ثم ورسول اللہ ﷺ حي. نسکت» (۱/ ۱۷۹)

[1] حاشية الطحطاوي على مراقي الفلاح وكلفظ (مشكوك فيه): نقل الطحطاوي في حاشيته: «قال ابن أمير حاج: هذه التسمية لم ترو عن سلفنا أصلاً، وإنما وقعت لكثير من المتأخرين فسماه بعضهم مشكوكاً وبعضهم مشكلاً ومرادهم بذلك التوقف»(۳۲/۱)

doubt in it), “tafwīḍ“[1] (deferment of interpretation),[2] and “al-tawaqquf al-sharʿī“[3] (suspended judgment of legal opinion), which find usage in Islamic jurisprudence and other fields and differ from tawaqquf within theology.

In the realm of theology, tawaqquf typically pertains to the position that something is ‘impossible to know' because the scripture being referred to does not provide explicit evidence either affirming or denying it. Consequently, delving into such matters is either not

[1] حاشية إتحاف المريد بجوهرة التوحيد لابن المؤلف عبد السلام اللقاني ، نقلاً عن مذهب أهل التفويض في الصفات للقاضي (١٥٢). والتفويض مصطلح يستخدم عند أهل التعطيل في أبواب الصفات غالباً؛ ويعني : «صرف اللفظ عن ظاهره مع عدم التعرض لبيان المعنى المراد منه، بل يترك ويفوض علمه إلى الله تعالى بأن يقول: الله أعلم بمراده»(۱۲۸)

حاشية البيجوري قال البيجوري: «(أوله)؛ أي: احمله على خلاف ظاهره مع بيان المعنى المراد. . . كما هو مذهب الخلف وهم من كانوا بعد الخمسمائة، وقيل : من بعد القرون الثلاثة .(أو فوض)؛ أي: بعد التأويل الإجمالي الذي هو صرف اللفظ عن ظاهره، فبعد هذا التأويل فوض المراد من النص الموهم إليه تعالى على طريقة وطريق الخلف أعلم وأحكم لما فيها مزيد الإيضاح والرد على السلف . . .الخصوم وهي الأرجح»(١٥٧).

“Mentioning the word without explaining its intended meaning, leaving it to God to know what is meant by it, and saying, ‘God knows best about His intention.'”

[2] In Islamic theology, the concepts of “tawaqquf” and “tafwīḍ” are not inherently contradictory, as tafwīḍ can be viewed as a response to tawaqquf. Thus, there exists an overlap between them, yet they can also be perceived as distinct notions within matters of belief and theology. Furthermore, they reflect differing approaches to comprehending and addressing specific aspects of faith. Here are the principal distinctions between tawaqquf and tafwīḍ:

Tawaqquf (Non-Commitment of Judgment):

- Tawaqquf is the approach of non-commitment judgment or refraining from making definitive theological statements on matters that are unclear or beyond human comprehension.

- It involves acknowledging that there may be issues or questions in Islamic theology that are not fully understood or explained in the religious texts (Quran and Ḥadīth) and that human reasoning may be insufficient to grasp the complete reality of certain matters.

- Those who adopt tawaqquf believe that it is better to avoid making speculative or dogmatic claims about such issues, as doing so might lead to misunderstandings or misinterpretations of the faith.

Tafwīḍ (Delegation or Entrustment):

- Tafwīḍ is the approach of delegating or entrusting the understanding of complex theological matters to Allāh ﷻand His divine wisdom when the texts apparent meaning is problematic and contradictory.

- It involves accepting that Allāh ﷻ possesses complete knowledge and wisdom, and that humans should not attempt to fully comprehend or rationalize matters that are considered beyond human intellect and understanding and seem problematic.

- Those who practice tafwīḍ believe that it is their duty to submit to God's will and trust that God's actions and decisions are just and wise, even if they do not fully understand the underlying reasons.

[3] Al-Tawaqquf al-sharʿī is the act of refraining from making a judgment when faced with conflicting evidence. It represents a form of hesitation or indecision, albeit temporary, while awaiting additional evidence or arguments that may sway the balance in favour of one possibility over another. For instance, when confronted with two conflicting ahaḍīth, a haḍīth scholar may opt to reserve judgment, recognizing their inability to reconcile the contradiction at hand. However, this abstention does not preclude the possibility of another scholar, at a later time, or with different insights, successfully resolving the discrepancy. In this context, al-tawaqquf al-sharʿī involves a deferral of judgment, acknowledging that a solution may be attainable but is postponed either for another individual or a later period.

permitted or considered a futile pursuit, as ‘there is no solid knowledge available to affirm or deny it.'[1] For the purpose of this essay, we will exclusively refer to tawaqquf as it is used in theology.

Types of Tawaqquf in Theology

Tawaqquf in theology can be classified into two categories: maḥmūd (praiseworthy/commendable) and madhmūm (blameworthy/condemned).

Maḥmūd (Praiseworthy) Tawaqquf:

Obligatory Restraint (al-tawaqquf al-wājib): This form of tawaqquf relates to matters where knowledge resides exclusively with Allāh ﷻ, encompassing subjects such as the attributes of Allāh ﷻ and certain aspects of the unseen. When it becomes impossible to definitively ascertain the truth in such matters or when discussing them may potentially lead to public harm (mafsadah), theologians deem silence not merely a recommendation but an imperative duty. To illustrate, consider the discussion of specific attributes of Allah, where silence is mandated due to the inherent impossibility of obtaining absolute knowledge or making conclusive determinations. This is reminiscent of an incident involving Imām Aḥmad (d. 241 AH)[1] when he was asked about the apparent contradiction between his belief in Prophet’s cousin, and son-in law, ʿAlī's rightful Imāmat and the fact that the companions of the Prophet, Ṭalḥa and Zubayr, disobeyed ʿAlī but rather opposed him. Imām Aḥmad, may Allāh ﷻhave mercy upon him, responded, “I have not entangled myself in their dispute in any manner.” His response signified his refusal to meddle in the disagreements they held, recognizing that they possessed superior knowledge in areas of interpretation and ijtihād. He acknowledged his lack of involvement in their conflicts and chose instead to focus on seeking forgiveness for them, maintaining a sincere heart towards them, and adhering to the commandment of loving and supporting them. It is important to emphasize that despite the virtues and merits of the individuals involved, the belief in ʿAli's leadership and Imāmat is firmly substantiated by textual

[1]المحصول الرازي في المحصول تعقب من قال أن الوقف ليس بحكم وذكرالخلاف فيه فقال: وهذا الوقف تارة يفسر بأنه: لا حكم، وهذا لا يكون وقفاً بل قطعاً بعدم الحكم، وتارة : بأنا لا ندري هل هناك حكم أم لا؟ وإن كان هناك حكم فلا ندري أنه إباحة أو حظر، لنا: أن قبل الشرع ما ورد خطاب الشرع فوجب أن لا يثبت شيء من الأحكام لما ثبت أن هذه الأحكام لا تثبت إلا الشرع»((1/ 160)

المستصفى والغزالي انتقد القول الذي ذكره الرازي بأنا لا ندري أنه إباحة أو حظر فقال: «وإن أريد به أنا نتوقف فلا ندري أنها محظورة أو مباحة فهو خطأ لأنا أنه لا حظر، إذ معنى الحظر : قول الله تعالى: (لا تفعلوه)، ولا إباحة :ندري إذ معنى الإباحة قوله: (إن شيء تم فافعلوه وإن شيء تم فاتركوه) ولم يرد شيء من ذلك»(١/ ٥٢).

[1] Imām Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal, was a Sunni Muslim polymath, renowned as a scholar, jurist, theologian, traditionist, and ascetic. He is revered as the eponym of the Hanbali school of Islamic jurisprudence, one of the four major orthodox legal schools of Sunni Islam. Regarded as the most highly influential and active scholar during his lifetime, Imam Ahmad's legacy extends far beyond his era. He is widely recognized as one of the most venerated intellectual figures in Islamic history, whose profound influence resonates across nearly every facet of traditionalist perspective within Sunni Islam.

- evidence, and that which is established by textual evidence must be faithfully followed.[1]

- Recommended and Permissible Restraint (al-tawaqquf al-mustaḥab w’al-mubāḥ): This category of tawaqquf is employed when there is a potential for benefit and a strong likelihood of harm. In more critical cases, as mentioned earlier under al-tawaqquf al-wājib, where either the benefit cannot be realised or the risk of harm is considerably high, restraint shifts from being merely recommended to becoming an obligatory course of action. A case in point is the response of Imām Mālik (d. 179 AH)[2] when queried about the statement of the Prophet ﷺ to ʿAli, “You are to me like Ḥārūn was to Musā,” and its interpretation. Imām Mālik replied, “This is the narration as it came.” [3] Similarly, when asked about the statement of the Prophet ﷺ concerning ʿAli's leadership (mawlā), Imām Mālik advised, “Do not speak about this; leave the ḥadīth as it came.”[4]

While scholars have provided comprehensive explanations for these hadiths and have engaged in insightful discussions about them, Imām Aḥmad recommended maintaining silence when individuals inquired about them. This was done to prevent unnecessary debates and potential misinterpretations by some individuals. Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 728 AH)[5] also commented on this matter, asserting that silence is a

[1]مجموع الفتاوى [ابن تيمية] كما ورد عن الإمام أحمد الله حين لامه من لامه لأنه لم يربع في الفضل بعلي ه: «قال له بعضهم: إذا قلت : كان إماماً واجب الطاعة ففي ذلك طعن على طلحة والزبير بث لم يطيعاه بل قاتلاه! فقال لهم أحمد الله : إني لست من حربهم في شيء؛ يعني: أن ما تنازع فيه علي وإخوانه لا أدخل بينهم فيه؛ لما بينهم من الاجتهاد والتأويل الذي هم أعلم به مني، وليس ذلك من مسائل العلم التي تعنيني حتى أعرف حقيقة حال كل واحد منهم، وأنا مأمور الاستغفار لهم وأن يكون قلبي لهم سليماً، ومأمور بمحبتهم وموالاتهم، ولهم من السوابق والفضائل ما لا يهدر؛ ولكن اعتقاد خلافته وإمامته ثابت بالنص وما ثبت بالنص وجب اتباعه (٤٤٠/٤)

[2] Imām Mālik ibn Anas, born in Medina, was a revered Sunni Muslim scholar, jurist, and theologian. He is celebrated as the founder of the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence, one of the four major orthodox legal schools of Sunni Islam. Renowned for his vast knowledge of ḥadīth and fiqh, Imām Mālik's contributions to Islamic jurisprudence are widely recognized. During his lifetime, Imām Malik became one of the most influential scholars of his era, earning profound respect and admiration. His seminal work, the Muwatta Imām Mālik, remains one of the most authoritative compilations of ḥadīth and legal opinions in Sunni Islam. Imām Mālik's teachings and principles continue to shape the practice of Islamic law and jurisprudence to this day, making him an enduring figure in the history of Islamic scholarship.

[3] السنة للخلال جاء عند الخلال أن المروذي، قال: «سألت أبا عبد الله عن قول النبي ﷺ لعلي: «أنت مني بمنزلة هارون من موسى» أيش تفسيره؟ قال :ذا الخبر، كما جاء»((٣٤٧/٢)، برقم (٤٦١))

[4] وكذلك سئل عن «قول النبي ﷺ لعلي : «من كنت مولاه فعلي مولاه»، ما وجهه؟ قال: لا تكلم في هذا ، دع الحديث كما جاء» أخرجه أحمد (۷۱/۲)، برقم (641)، وابن ماجه (٤٥/١)، برقم (۱۲۱)، والترمذي (74/6)، برقم (۳۷۱۳)، والنسائي (411/7)، برقم (8343)، قال الذهبي: متنه متواتر، السير (٣٣٥/٨) وقال الأرناؤوط في مسند أحمد: صحيح جاء عن ثلاثين صحابياً .

[5] Ibn Taymiyyah, Taqī al-Dīn Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm ibn ʿAbd al-Salām al-Harrānī al-Dimashqī, was a prominent Islamic scholar, theologian, and jurist of the medieval period. He was born in Harran, in present-day Turkey. Known for his vast knowledge of Islamic sciences, Ibn Taymiyyah made significant contributions to various fields, including theology, jurisprudence, Quranic exegesis, and ḥadīth studies. He was deeply influenced by the teachings of earlier scholars, particularly the Hanbali school of jurisprudence. Ibn Taymiyyah's staunch adherence to Qurān and Sunnah and his emphasis on the purification of Islamic practices from innovations earned him both admiration and criticism during his lifetime. Ibn Taymiyyah's prolific writings cover a wide range of subjects, including theology, Islamic law, Sufism, and political theory. His works reflect his rigorous analytical approach and his efforts to uphold what he perceived as the authentic teachings of Islam. He became known for his sharp critiques of theological and philosophical deviations within Islamic thought, as well as his outspoken stance against practices he deemed contrary to Islamic principles. His teachings continue to resonate with contemporary Muslim scholars and have sparked ongoing debates on issues of theology, jurisprudence, and Islamic reform.

In both forms of praiseworthy tawaqquf, the position of non-commitment is adopted because it aligns with scriptural evidence (naṣṣ). In situations where there is neither an explicit nor implicit text that definitively affirms or denies a particular position, restraint becomes either obligatory or recommended. This approach ensures scholarly integrity and prevents unnecessary discord while upholding the essence of tawaqquf.[1]

Madhmūm (Blameworthy) Tawaqquf:

- Non-Commitment Leading to Disbelief (al-tawaqquf al-kufrī): This category arises when maintaining a stance of non-commitment amounts to disbelief (kufr). It encompasses fundamental matters of belief and creed, where multiple sources within scripture strongly corroborate the tenets of faith. Refraining from affirming the absolute oneness of Allah, His lordship, divinity, or denying the finality of prophethood, the existence of paradise and hellfire, and other fundamental aspects of faith falls within this category.

For instance, asserting uncertainty about Allah's location, as in saying, “I don't know if my Lord is in the heavens or on the earth,” is considered an act of disbelief. Similarly,

criticism during his lifetime. Ibn Taymiyyah's prolific writings cover a wide range of subjects, including theology, Islamic law, Sufism, and political theory. His works reflect his rigorous analytical approach and his efforts to uphold what he perceived as the authentic teachings of Islam. He became known for his sharp critiques of theological and philosophical deviations within Islamic thought, as well as his outspoken stance against practices he deemed contrary to Islamic principles. His teachings continue to resonate with contemporary Muslim scholars and have sparked ongoing debates on issues of theology, jurisprudence, and Islamic reform.

[1] Other examples where tawaqquf is recommended (mustaḥab) or permissible (mubāḥ)

Recommended:

- Do pious people enjoy a higher status than angels?

- Are the virtuous Jinn admitted into Paradise in the Hereafter?

- Is Arabic the language of the Hereafter?

- Will Moses be spared the general death when the trumpet is blown on the day of Resurrection?

Permissible:

- Was God seen directly on the night of prophetic ascension?

- Do animals have rational souls?

- Are animals recompensed for the suffering they undergo in life?

- What type of fruit did the tree in the Garden bear?

- Was Prophet Ādams’s Garden in heaven or on Earth?

[1] الفتاوى الكبرى قول ابن تيمية رحاله : «ولهذا يسع الإنسان في مقالات كثيرة لا يقر فيها بأحد النقيضين لا ينفيها ولا يثبتها، إذا لم يبلغه أن الرسول نفاها أو أثبتها ، ويسع الإنسان السكوت عن النقيضين في أقوال كثيرة إذا لم يقم دليل شرعي بوجوب قول أحدهما» (351/6).

doubting the status of certain individuals as messengers or expressing uncertainty about the fate of disbelievers in the afterlife is also deemed disbelief. Imām Abū Ḥanīfah (d. 150 AH)[1], for example, maintained that anyone who says, “I don't know whether my Lord is in the heavens or on the earth,” has committed an act of disbelief. Likewise, those who claim that Allāh ﷻis on the Throne but are uncertain about whether the Throne is in the heavens or on the earth also fall into this category[2].

Ibn Taymiyyah elaborated on this, noting that if someone were to ask, “Is someone who says, ‘I don't know if the disbeliever is a disbeliever?' [considered a disbeliever]?” Abū Ḥanīfah would reply, “He is like [the disbeliever].” Ibn Taymiyyah added that it was asked, ‘What if someone says, ‘I don't know where the fate of the disbeliever will be?' Abū Ḥanīfah said, ‘He denies the Book of Allāh ﷻ and is a disbeliever.'”[3]

Additionally, Ibn Taymiyyah stated, “Whoever believes in everything that must be believed but says, ‘I don't know if Musā and Īsā were messengers or not,' is a disbeliever. And whoever says, ‘I don't know if the disbeliever will be in paradise or in hell,' is a disbeliever, as indicated by the verse, ‘Those who disbelieve, for them is the fire of Hell. They will neither die therein nor live.' [Fāṭir: 36]. And He also said, ‘And for them is a painful punishment.' [Al-Shūra: 16].” [4]

[1] Imām Abū Ḥanīfah, also known as Abū Ḥanīfah al-Nu'mān ibn Thābit, was a prominent Islamic scholar and jurist of the early Islamic period. He was born in the city of Kūfa, Irāq. He is revered as the founder of the Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence, one of the four major Sunni legal schools. His legal methodology emphasised the use of reason and analogy (qiyas) alongside scripture to derive legal rulings. This approach earned him recognition as one of the greatest jurists in Islamic history. Throughout his life, Abū Hanīfah gained a reputation for his piety, humility, and dedication to scholarship. Abū Ḥanīfah’s contributions to Islamic jurisprudence include the development of systematic legal principles and methodologies, as well as the compilation of his renowned legal compendium, Al-Fiqh al-Akbar. His legal opinions and rulings, collected by his students, formed the basis of the Hanafi school's legal doctrine.

[2] الفقه الأبسط ما جاء عن أبي حنيفة الله قوله: «من قال لا أعرف ربي في السماء أم في الأرض فقد كفر، وكذا من قال إنه على العرش ولا أدري العرش أفي السماء أم في الأرض» (135).

[3] الفقه الأبسط مطبوع مع الشرح الميسر على الفقهين الأبسط والأكبر المنسوبين لأبي حنيفة تأليف محمد بن عبد الرحمن الخميس) المؤلف: ينسب لأبي حنيفة النعمان وسأل أبا حنيفة الله كذلك سائل فقال: «إن قال قائل: لا أعرف الكافر كافراً؟ قال: هو مثله . قلت : فإن قال: لا أدري أين مصير الكافر؟ قال: هو جاحد لكتاب الله تعالى وهو كافر» (114 – 115).

[4] الفقه الأبسط. من آمن بجميع ما يؤمن به، إلا أنه قال: لا أعرف موسى وعيسى أمرسلان هما أم غير مرسلين! فهو كافر، ومن قال: لا أدري الكافر أهو في الجنة أو في النار! فهو كافر، لقوله تعالى والذين كفروا لهم ناز جهنم لا يقضى عليهم فيموتوا فـاطـر: 36] وقـال : ولهم عذاب الحريق ( [البروج : 10] وقال الله تعالى: «ولهم عذاب شديد ( [الشورى: 16]» (١٢٦)

In the context of his father's beliefs, Ibn Abū Ḥātim (d. 327 AH)[1] mentioned that “whoever doubts the speech of Allāh ﷻ and remains in doubt, saying, ‘I don't know if it (the Qur’ān) is created or uncreated,' is a Jahmī.” [2]

This category underscores the gravity of non-commitment when it leads to disbelief in fundamental aspects of faith, and it serves as a stark reminder of the significance of firm adherence to core theological principles.

- Non-Commitment Leading to Innovation (al-tawaqquf al-bidʿī): This form of tawaqquf pertains to theological matters that diverge from the sunnah (traditions of the Prophet) but do not reach the level of disbelief, and/or go against the consensus (ijmāʿ) of the early Islamic scholars (salaf). In these cases, even though the scripture may not explicitly state a particular viewpoint, the Ahl al-Sunnah w’al-Jamāʿa (the mainstream Sunni Muslim community) are in agreement that the intended meaning is clear, and any alternative interpretation would constitute a deviation and misguidance. [3] While such non-commitment doesn't amount to disbelief, it falls within the categories of innovation (bidʿa).[4]

For instance, having a non-committal stance regarding the superiority of the Rightly Guided Caliphs over others or expressing uncertainty about the faith of apparent Muslims without clear evidence falls into this category. Scholars like Ibn Taymiyyah emphasised that certain matters, which run contrary to consensus, ijmāʿ, should not

[1] Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Muhammad ibn Idris ibn al-Mundhir ibn Dāwūd ibn Mihrān al-Tamīmi al-Hanzali al-Rāzī (240 AH – 327 AH), known as Ibn Abī Ḥātim, hailed from a lineage deeply rooted in Islamic scholarship. His father, Abū Ḥātim al-Rāzī, was an esteemed scholar renowned for his expertise in ḥadīth, criticism, narrators' biographies, and the study of ḥadīth anomalies. Ibn Abi Hatim followed in his father's footsteps, dedicating himself to the pursuit of ḥadīth knowledge with unparalleled dedication. His travels in search of ḥadīth spanned vast distances, as he tirelessly traversed regions from Kūfa to Baghdad, Makkah to Medina, Bahrain to Egypt, and beyond, accumulating a wealth of ḥadīth knowledge. Ibn Abi Hatim's relentless quest for Ḥadīth knowledge culminated in the compilation of his seminal work, “Sunan,” and his refutation of the Jahmiyya sect, aligning firmly with the creed of Ahl al-Sunnah wa al-Jamā'ah. His approach to Quranic exegesis emphasized reliance on authenticated narrations traced back to the Prophet Muḥammad ﵆, his companions, or the Successors, thereby adhering to the methodology of the Salaf. Ibn Abī Ḥātim's theological stance and scholarly endeavours reflect his unwavering commitment to the creed of Ahl al-Sunnah wa al-Jamā'ah, as evidenced in his written works.

[1] شرح أصول اعتقاد أهل السنة وجاء عن ابن أبي حاتم في ذكره لاعتقاد أبيه أبي حاتم وأبي زرعة :«من شك في كلام الله ﷿ فوقف شاكا فيه يقول: لا أدري مخلوق أو غير مخلوق فهو جهمي» (۲۰۰/1).

[1]مجموع الفتاوى [ابن تيمية] فما ثبت عنه من السنة فعلينا اتباعه؛ سواء قيل إنه في القرآن؛ ولم نفهمه نحن أو قيل ليس في القرآن؛ كما أن ما اتفق عليه السابقون الأولون والذين اتبعوهم بإحسان؛ فعلينا أن نتبعهم فيه؛ سواء قيل إنه كان منصوصا في السنة ولم يبلغنا ذلك أو قيل إنه مما استنبطوه واستخرجوه باجتهادهم من الكتاب والسنة. (5:163)

[1] Some examples are to hold tawaqquf on issues like the vision of Allāh ﷻin the Hereafter, the denial of vision of Allāh ﷿in the this world, on the issue of the accountability (taklīf) of jin and their punishment and many others as there is ijmāʿ of the Ahl al-Sunnah on these matters.

be subject to tawaqquf. For example, denying the caliphate of Ali or expressing uncertainty about it is considered an innovation.

Ibn Taymiyyah expounded on this issue, quoting ʿAbd Allāh bin Masʿūd who stated, “Loving Abū Bakr and ʿUmar and recognising their virtue is part of the Sharīʿah, for the Prophet ﷺ said, ‘Follow those who come after me, Abū Bakr and ʿUmar.' Therefore, acknowledging their virtue over those who followed them is obligatory, and maintaining a non-committal position about it is not permissible.” However, regarding ‘Uthmān and ʿAlī, there were differing opinions on whether having a non-committal stance about their virtue was permissible. [1]

Anyone persistently holding a non-committal stance about the virtue of the two Shaykhs (Abū Bakr and ʿUmar) over others or expressing uncertainty about ʿAlī's caliphate is engaging in innovation. Ibn Taymiyyah also highlighted the innovation of those who adopt a non-committal position concerning ʿAlī's caliphate.

Regarding those who remained silent about ʿAlī's calīphate, Ibn Taymiyyah mentioned that Imām Ahmad had a clear stance on the matter, considering it an innovation for someone to maintain a non-committal position about Ali's caliphate. Ahmad explicitly stated that those who did so were misguided, and he advocated boycotting and discouraging support for them. Ahmad and other early scholars (salaf) firmly believed that Ali was more deserving of the caliphate, leaving no room for doubt. [2]

Another issue that falls within this category is having a non-committal position on the created nature of the Quran, particularly when done out of ignorance. Abū Ḥātim and Abu Zurʿah (d. 289 AH)[3] ruled that someone who maintains a non-committal stance on the created nature of the Qurān, despite being knowledgeable about it, is guilty of innovation. However, for those who do so out of ignorance, their judgment is milder, and it has been narrated that they are not considered disbelievers. [4]

In summary, maḥmūd (praiseworthy) tawaqquf involves either obligatory or recommended restraint in theology when explicit scriptural evidence is lacking to affirm or deny a position.

[1] مجموع الفتاوى قول ابن تيمية رحله : «قال عبد الله بن مسعود ه : حب أبي بكر وعمر ا ومعرفة فضلهما من الشئة؛ أي: من شريعة النبي ﷺ التي أمر بها فإنه قال: «اقتدوا باللذين من بعدي : أبي بكر وعمر» ولهذا كان معرفة فضلهما على من بعدهما واجباً لا يجوز التوقف فيه بخلاف عثمان وعلي ففي جواز التوقف فيهما قولان (4/ 435).

مجموع الفتاوى [ابن تيمية] الإجماع وهو متفق عليه بين عامة المسلمين من الفقهاء والصوفية وأهل الحديث والكلام وغيرهم في الجملة وأنكره بعض أهل البدع من المعتزلة والشيعة لكن المعلوم منه هو ما كان عليه الصحابة وأما ما بعد ذلك فتعذر العلم به غالبا ولهذا اختلف أهل العلم فيما يذكر من الإجماعات الحادثة بعد الصحابة واختلف في مسائل منه كإجماع التابعين على أحد قولي الصحابة والإجماع الذي لم ينقرض عصر أهله حتى خالفهم بعضهم والإجماع السكوتي وغير ذلك (11:341)

[2] مجموع الفتاوى المنصوص عن أحمد تبديع من توقف فيخلافة علي وقال: هو أضل من حمار أهله وأمر بهجرانه ونهى عن ولم يتردد أحمد ولا أحد أئمة الشئة في أنه ليس غير علي ﷺ أولى بالحق منه ولا شكوا في ذلك» (4:438)

[3] Abu Zurʿah al-Rāzī (207 AH – 289 AH) was a renowned hadith scholar known for his reliability and vast knowledge. He traveled extensively and narrated from numerous scholars. His narrations are found in the major hadith collections, with Muslim directly narrating one hadith from him. Abu Zurʿah passed away three years after Muslim, highly praised for his piety, devotion, and strong memory.

[4] شرح أصول اعتقاد أهل السنة روى عنهم ذلك ابن أبي حاتم: «من وقف في القرآن جاهلا علم وبدع ولم يكفر»(1:200)

[1] Abu Zurʿah al-Rāzī (207 AH – 289 AH) was a renowned hadith scholar known for his reliability and vast knowledge. He traveled extensively and narrated from numerous scholars. His narrations are found in the major hadith collections, with Muslim directly narrating one hadith from him. Abu Zurʿah passed away three years after Muslim, highly praised for his piety, devotion, and strong memory.

[1] شرح أصول اعتقاد أهل السنة روى عنهم ذلك ابن أبي حاتم: «من وقف في القرآن جاهلا علم وبدع ولم يكفر»(1:200)

Madhmūm (blameworthy) tawaqquf encompasses disbelief when applied to fundamental beliefs and heresy or innovation when applied to issues conflicting with the sunnah and the consensus of early scholars. These distinctions help clarify the theological significance of tawaqquf in various contexts.

Inappropriate Application of Tawaqquf

Tawaqquf may be ‘misapplied’ تحريف (taḥrīf) or تطبيق خاطئ (taṭbīq khaṭī’), primarily due to a failure to distinguish between the application of tawaqquf to the word (lafẓ) and its application to the affirmed meaning (maʿna) in scripture. “Misapplied” suggests that there's a failure to correctly apply the concept of tawaqquf due to a lack of distinction between its application to the word (lafẓ) and its application to the affirmed meaning (maʿna) in scripture.

And/ or it may be ‘misrepresented’ تشويه (tashwīh) or تحريف الدلالة (taḥrīf al-dalālah), where there is a desire to allow alternate interpretations of a statement despite a lack of room for such interpretations. “Misrepresented” implies that there's an intentional distortion or misinterpretation of tawaqquf, perhaps to accommodate alternate interpretations of a statement where there isn't room for such interpretations according to the original intent or context.

- Misapplication of Tawaqquf:

Tawaqquf in Both Word and Meaning: In certain cases, tawaqquf pertains to both the word (lafẓ) and its meaning. An example is the discussion of the attributes of Allah. In this context, according to some, there is a non-commitment not only to the wording used to describe Allāh ﷻbut also to the meaning conveyed by those words.[1]

[1] Ambiguity in the Qurān can be attributed to both the wording (lafẓ) and the meaning (maʿna), and sometimes it can involve both simultaneously. If there is ambiguity, then there is simultaneously the need to make tawaqquf on fundamental issues of creed where the ambiguity is not definitively clarified.

- The first category of ambiguity refers to cases where the ambiguity arises from the wording itself, which can be either in singular or compound form. Singular form ambiguity may arise due to the unusual nature of the word or its multiplicity of meanings. Compound form ambiguity may occur due to its brevity, expansion, or arrangement.

- The second category deals with cases where the ambiguity arises from the meaning alone. Examples include descriptions of Allāhﷻ , the horrors of the Day of Judgment, the delights of Paradise, and the punishment of Hell. These are beyond human comprehension, and it is impossible for the human intellect to fully grasp the realities of these matters.

- The third category involves cases where the ambiguity arises from both the wording and the meaning together. An example given is the verse: “It is not righteousness that you enter the houses from the back, but righteousness is in one who fears Allāhﷻ.” (Qurān, 2:189) This verse may not be fully understood without knowledge of the customs of the pre-Islamic Arabs. Some of the Ansar used to enter their homes through a hole in the wall, while others entered from the front. This verse clarifies the correct approach and the virtue of righteousness, but without knowledge of the context, its meaning may remain obscure.

مناهل العرفان في علوم القرآن [الزرقاني، محمد عبد العظيم] منشأ التشابه وأقسامه وأمثلته[

نعلم مما سبق أن منشأ التشابه إجمالا هو خفاء مراد الشارع من كلامه أما تفصيلا فنذكر أن منه ما يرجع خفاؤه إلى اللفظ ومنه ما يرجع خفاؤه إلى المعنى ومنه ما يرجع خفاؤه إلى اللفظ والمعنى معا.

فالقسم الأول وهو ما كان التشابه فيه راجعا إلى خفاء في اللفظ وحده منه مفرد ومركب والمفرد قد يكون الخفاء فيه ناشئا من جهة غرابته أو من جهة اشتراكه والمركب قد يكون الخفاء فيه ناشئا من جهة اختصاره أو من جهة بسطه أو من جهة ترتيبه…

والقسم الثاني هو ما كان التشابه فيه راجعا إلى خفاء المعنى وحده مثاله كل ما جاء في القرآن الكريم وصفا لله تعالى أو لأهوال القيامة أو لنعيم الجنة وعذاب النار فإن العقل البشري لا يمكن أن يحيط بحقائق صفات الخالق ولا بأهوال القيامة ولا بنعيم أهل الجنة وعذاب أهل النار وكيف السبيل إلى أن يحصل في نفوسنا صورة ما لم نحسه وما يكن فينا مثله ولا جنسه؟ …

القسم الثالث وهو ما كان التشابه فيه راجعا في اللفظ والمعنى معا له أمثلة كثيرة منها قوله عز اسمه: {وليس البر بأن تأتوا البيوت من ظهورها} فإن من لا يعرف عادة العرب في الجاهلية لا يستطيع أن يفهم هذا النص الكريم على وجهه ورد أن ناسا من الأنصار كانوا إذا أحرموا لم يدخل أحد منهم حائطا ولا دارا ولا فسطاطا من باب فإن كان من أهل المدر نقب نقبا في ظهر بيته يدخل ويخرج منه وإن كان من أهل الوبر خرج من خلف الخباء فنزل قول الله: {وليس البر بأن تأتوا البيوت من ظهورها, ولكن البر من اتقى, وأتوا البيوت من أبوابها, واتقوا الله لعلكم تفلحون} .

فهذا الخفاء الذي في هذه الآية يرجع إلى اللفظ بسبب اختصاره ولو بسط لقيل وليس البر بأن تأتوا البيوت من ظهورها إذا كنتم محرمين بحج أو عمرة ويرجع الخفاء إلى المعنى أيضا لأن هذا النص على فرض بسطه كما رأيت لا بد معه من معرفة عادة العرب في الجاهلية وإلا لتعذر فهمه. (2:278)

[1] Other verses (Q. 3:173), (Q. 48:4), (Q. 9:124) also explicitly state that imān increases but there are no verses which explicitly state that imān decreases.

[1] الشريعة المؤلف: أبو بكر محمد بن الحسين بن عبد الله الأجري البغدادي ، المحقق: الدكتور عبد الله بن عمر بن سليمان الدميجي، الناشر: دار الوطن – الرياض – السعودية، الطبعة الثانية، ١٤٢٠هـ – ۱۹۹۹م. جاء عند الآجري: «قيل لسفيان بن عيينة :الإيمان يزيد وينقص؟ قال: أليس تقرؤون القرآن فزادهم إيمانا في غير موضع، قيل: ينقص؟ قال: ليس شيء يزيد إلا وهو ينقص»(٦٠٥/٢)، برقم (٢٠٤).

شرح أصول اعتقاد أهل السنة جاء ذكر نقصان الإيمان عن الصحابة باستفاضة، فضلاً عمن بعدهم، ورواه اللالكائي عن ستة عشر صحابياً، وثمانية وعشرين تابعياً، وأكثر من أئمة الإسلام بعدهم، منهم: الشافعي، والأوزاعي، والثوري، ووكيع، وابن المبارك، وأحمد بن حنبل، وابن راهويه ، أربعين من وحماد بن سلمة ، والبخاري، وغيرهم (٩٦٢/٥) وقد ذكر بعد ذلك عن عقبة بن عامر الجهني ه ولم يذكره في هذا الموضع، ولم ينبه عليه المحقق، فصار المروي عنهم عنده : سبعة عشر صحابياً .

فعن عمير بن حبیب قال: «الإيمان يزيد وينقص، قيل له: ما زيادته ونقصانه؟ قال: إذا ذكرنا الله وحمدناه وسبحناه فذلك زيادته، وإذا غفلنا ونسينا فذلك نقصانه»المرجع السابق (۱٠٢٠/٥)، برقم (۱۷۲۱) وذكر المحقق من أخرجه غيره بأسانيد مختلفة

[1] Can be argued that the reason it affirms decrease in imān is because it necessarily infers that with increasing imān that there will be decreasing imān see– this is not the case with absolute decent from Prophet Ādam vs relative descent.

understood and established, even though it is not explicitly stated in scripture. This is the situation where there is “dalātahu ʿalayhā mafhūman lā manṭūqan” (its implication is understood and unanimously agreed but not explicitly stated).[1] Here, tawaqquf is related to the wording but not to the meaning, which is definitively affirmed. Going against this understanding requires substantial evidence (ḥujjah).

The word “deficiency” (النقص) is not mentioned in the Qurān, so there is tawaqquf concerning confirming the word itself in the Qur’ān, but not in confirming the meaning of deficiency which is implied. This is not unique, as contemporaries of Sufyan ibn ‘Uyaynah (d. 198 AH)[2] questioned this (i.e. confirmation of the wording of deficiency in the Qur’ān) and asked him for textual evidence. Ibn al-Mubārak (d. 181 AH)[3] also exercised tawaqquf regarding the wording of deficiency, as mentioned by Ibn Taymiyyah in his travels. He said, “The companions have been affirmed to have said that faith can increase and decrease.” This is the view of the majority of scholars. Ibn al-Mubārak used to say, “It can vary and increase, and he refrains from using the word ‘decrease.' Imām Māik, in his belief, has two narrations: one that it does not decrease, and the Qurān has spoken of increase in places. The proof is that texts also indicate its decrease, as in the saying: ‘The adulterer does not commit adultery when he commits adultery while being a believer,' and similar statements. However, this word is only known in the Qurān in His saying in Sūrah Al-Nisā’: ‘Deficient in intelligence and religion,' and they interpreted deficiency in her religion to mean that when she menstruates, she does not fast or pray, and in this way, several scholars have argued that there is a decrease.” [4]

[1] معارج القبول.واستدرك العلامة حافظ الحكمي الله على دلالته الصريحة فقال :«وقال النسائي : باب زيادة الإيمان ذكر فيه حديث الشفاعة، ودلالته منطوقاً على تفاضل أهل الإيمان فيه، وأما الزيادة والنقص فدلالته عليها مفهوماً لا منطوقاً (۳/ ۱۱۷۸)

وكذلك حديث : «نافق حنظلة» يدل على نقصان الإيمان وإن لم يصرح بلفظ النقص . أخرجه مسلم (٢١٠٦/٤)، برقم (٢٧٥٠).

[2] Sufyān ibn ʿUyaynah (سفيان بن عُيينة) was a prominent scholar of ḥadīth and jurisprudence in the early Islamic period. He was born in the year 107 AH (after Hijra) and passed away in the year 198 AH. was a prominent eighth-century Islamic religious scholar from Mecca. He was from the third generation of Islam referred to as the tabiʿ al-tabiʿīn, “the followers of the followers”. He specialized in the field of ḥadīth and Quran exegesis and was described by al-Dhahabi as Shaykh al-Islām—a preeminent Islamic authority. Some of his students achieved much renown in their own right, establishing schools of thought that have survived until the present.

[3] Ibn al-Mubārak (ابن المبارك), whose full name is ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Mubārak, was a renowned scholar of ḥadīth and Islamic jurisprudence. He was born in the year 118 AH (after Hijra) and passed away in the year 181 AH. was an 8th-century Sunni Muslim scholar and theologian. Known by the title Amīr al-Mu'minin fi al-Ḥadīth, he is considered a pious Muslim known for his memory and zeal for knowledge who was a muhaddith and was remembered for his asceticism. His teachers included Sufyān al-Thawrī and Abū Hanīfah.

[4] مجموع الفتاوى. وهو لم ينفرد بهذا، فقد سبق أن معاصري سفيان بن عيينة استشكلوا ذلك وسألوه عليه نصاً، وكذلك ابن المبارك توقف في النقص كما ذكر ابن تيمية رحاله : «والصحابة قد ثبت عنهم أن الإيمان يزيد وينقص وهوقول أئمة الشئة وكان ابن المبارك يقول: هو يتفاضل ويتزايد ويمسك عن لفظ ينقص، وعن مالك في كونه لا ينقص روايتان، والقرآن قد نطق بالزيادة في غير موضع، ودلت النصوص على نقصه كقوله: «لا يزني الزاني حين يزني وهو مؤمن» ونحو ذلك لكن لم يعرف هذا اللفظ إلا في قوله في النساء «ناقصات عقل ودين» وجعل من نقصان دينها أنها إذا حاضت لا تصوم ولا تصلي وبهذا استدل غير واحد على أنه ينقص» (١٣/٥٠ – ٥١)

An example of the misapplication of tawaqquf can be observed in discussions involving dinosaurs, as illustrated by Shoaib Malik. He argues that Islamic scripture neither affirms nor denies the existence of dinosaurs, thus rendering attempts to argue for or against them on scriptural grounds invalid. The claim is that the Qurān and ḥadīth remain entirely silent on this subject, rendering it inappropriate and, indeed, sinful to invoke scripture in such discussions. Claiming either the denial or mandated belief in dinosaurs within Islam lacks scriptural support.[1]

Comparing the issue of dinosaurs to theological concepts where tawaqquf is typically applied constitutes a false analogy. The crucial distinction lies in the presence or absence of scriptural references. Tawaqquf in Islamic theology typically pertains to matters addressed in scripture, whether explicitly or implicitly, signifying their theological significance. In cases where the text is not explicit, tawaqquf may apply to the interpretation of wording or meaning, allowing for a non-committal stance on theological beliefs lacking definitive textual support.

In contrast, dinosaurs are not addressed in Islamic scripture. Neither the wording nor the meaning in scripture relates to the existence or non-existence of dinosaurs, making it inappropriate to employ tawaqquf terminology in this context. Essentially, Islam offers no direct teachings or guidance regarding dinosaurs because they are not discussed in the Qurān or ḥadīth.

The comparison between the lineage of Ādam and dinosaurs poses a significant challenge, as they hold distinct levels of relevance and importance within Islam. The lineage of Ādam is explicitly documented in Islamic scriptures, carrying profound theological significance through its recurrent mention. Conversely, dinosaurs find no mention in Islamic texts, leading scholars to generally overlook theological debates concerning them, unlike the lineage of Ādam, which delves into theological realms. The absence of scriptural references regarding dinosaurs sets them apart from theological matters where tawaqquf, or suspension of judgment, may apply. It underscores the fundamental disparity between the roles and implications of these two subjects in the context of Islamic theology.

- Misrepresentation of Tawaqquf:

Tawaqquf is not a tool to evade providing clear answers and accountability for one's beliefs, nor is it meant to allow theologians to hide behind ambiguity and avoid taking a firm stance on important theological matters. There are instances where individuals employ tawaqquf on the wording of scripture, even when explicit or implicit consensus exists among scholars. This tactic, whether intentional or unintentional, opens the door for alternative opinions or interpretations that may deviate from the intended literal or obvious meaning of the text. By

[1] Malik, S.A. Islam and Evolution, Al-Ghazālī and the Modern Evolutionary Paradigm, Routledge, London 2021, 134

asserting that scripture does not definitively confirm or deny a particular interpretation, these individuals indirectly challenge or reject the consensus interpretation or meaning of the text. Consequently, when tawaqquf is claimed in such cases, it paves the way for other interpretations, diverging from the consensus, without necessarily having equal or stronger evidential support. This can lead to the acceptance of these alternative interpretations on the premise that Islam maintains a stance of non-commitment on the issue.

For instance, Shoaib Malik generalises the concept of tawaqquf when he claims that “the take-home message with theological tawaqquf is that a Muslim cannot affirm nor negate such things using scripture because scripture itself isn’t saying anything. If so, all options are possible to take up since all are compatible with Islamic scripture. It is this understanding of tawaqquf that Jalajel uses to make his case for there being no conflict between Islam and evolution.” [1]

However, this assertion overlooks the nuanced nature of theological tawaqquf, which is a specific and qualified epistemological approach used by theologians. It is intended to be applied exclusively to the words of scripture and not to any arbitrary point of discourse lacking a direct relationship with scripture, such as the existence or non-existence of dinosaurs. Furthermore, the mere invocation of tawaqquf does not imply that any idea can be entertained in interpretation. Instead, it must adhere to a standardised hermeneutical approach in interpreting the text's wording, and there should be no imposition of restrictions on the implied meaning of the word due to consensus (ijmāʿ) among Muslim scholars.

A compelling example that illustrates the nuanced nature of tawaqquf in theology is the debate surrounding the created or uncreated nature of the Qurān. Abū Ḥātim (d. 277 AH)[2] and Abu Zurʿah (d. 264 AH)[3] held the position that someone who maintains a non-committal stance, tawaqquf, on the created nature of the Quran, despite possessing knowledge about it, is guilty of innovation, bidʿa. [4]

[1] Malik, S.A. Islam and Evolution, Al-Ghazālī and the Modern Evolutionary Paradigm, Routledge, London 2021, 134

[2] Abū Ḥātim Muḥammad ibn Idrīs al-Rāzī, (أبو حاتم الرازي), was a prominent scholar of ḥadīth and Islamic jurisprudence. He was born in the year 195 AH (after Hijra) and passed away in the year 277 AH. Abū Ḥātim al-Rāzī was highly respected for his knowledge, piety, and contributions to Islamic scholarship, particularly in the fields of ḥadīth criticism and authentication. He was a leading figure in the science of ḥadīth and played a significant role in preserving the authenticity of prophetic traditions.

[3] Abū Zur'ah Muāammad ibn al-Ḥusayn al-Dimashqī, (أبو زرعة الرازي), was a renowned scholar of ḥadīth and Islamic jurisprudence. He was born in the year 158 AH (after Hijra) and passed away in the year 264 AH. He was highly respected for his expertise in ḥadīth sciences and his contributions to the authentication and preservation of prophetic traditions. He was considered one of the leading authorities in the field of ḥadīth criticism during his time.

[4] شرج أصول اعتقادأهل السنة روى عنهم ذلك ابن أبي حاتم: «من وقف في القرآن جاهلا علم وبدع ولم يكفر»(1:200)

It's noteworthy that none of the scriptural proofs confirming that the Qur’ān is not created, in line with the consensus position, ijmāʿ of Ahl al-Sunnah w’al-Jamāʿa, are explicit. They are, instead, implicit meanings deduced from the Qur’ān by authoritative scholars well-versed in matters of creed or derived through rational deduction. [1] Yet, scholars have made serious statements about those who employ tawaqquf in an attempt to obscure or conceal the consensus position regarding the creation of the Qurān. Al-Khallāl (d. 311 AH)[2] reported from al-Mukhramī (d. 254 AH)[3]: “He said to Abū ʿAbdullah Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Ḥanbal: ‘al-wāqifah (those who do tawaqquf)?' He replied: ‘They are worse than the Jahmiyyah[4]; they concealed themselves with al-waqf (non-commitment).'”[5]

Furthermore, some have argued that proponents of theological innovation, bidʿa, would equate (1) those who adopt a position of non-commitment (i.e., al-wāqif) and (2) those who outright deny (i.e., al-Jahmi) the uncreated nature of the Qurān. This is because the ultimate

[1]. شرح القصيدة اللامية لابن تيمية – عبد الرحيم السلمي [عبد الرحيم السلمي] [الأدلة على أن القرآن كلام الله غير مخلوق[

والقرآن كما قلت: هو كلام الله عز وجل غير مخلوق، والسلف ينصون على هذا؛ لأن المعتزلة قالت: بأن القرآن مخلوق من الخلق، ويقولون: إن القرآن ليس صفة من صفات الله، بل هو خلق من خلقه، ويقولون: إن الله عز وجل خلق الكلام في الهواء فأخذه جبريل وجاء به إلى النبي صلى الله عليه وسلم، فالقرآن مخلوق.

ولا شك أن هذا باطل، ويدل على بطلان هذا أدلة كثيرة، منها: قول الله عز وجل: {ألا له الخلق والأمر} [الأعراف:٥٤]، ففرق بين الخلق والأمر، ولا شك أن القرآن من أمر الله وليس من خلقه، وهذا ما استدل به الإمام أحمد ومن قبله سفيان بن عيينة الهلالي رحمهما الله، فاستدلوا على أن القرآن ليس مخلوقا بالتفريق بين الخلق والأمر واعتبار الأمر غير الخلق، فالأمر صفة من صفات الله عز وجل كما أن الخلق صفة من صفاته، لكن لا يصح أن يقال في صفة: إنها مخلوقة.

الدليل الثاني: قول الله عز وجل: {الرحمن * علم القرآن * خلق الإنسان * علمه البيان} [الرحمن:١ – ٤]، والقرآن من البيان، ولهذا قال الإمام أحمد: القرآن من علم الله تعالى، واستدل على أنه من علم الله عز وجل بقول الله تعالى: {فمن حاجك فيه من بعد ما جاءك من العلم} [آل عمران:٦١]، والذي جاء النبي صلى الله عليه وسلم هو القرآن، فاعتبر القرآن من علم الله عز وجل، ومن قال: إن علم الله عز وجل مخلوق فلا شك في كفره؛ فإن علم الله عز وجل صفة من صفاته، وليس في صفات الله مخلوق؛ لأنه لو كان علم الله مخلوق لاقتضى هذا أن يكون الله سبحانه وتعالى مخلوق، تعالى الله عما يقولون علوا كبيرا، ولهذا يجب الحذر من هذه المقالة البدعية الضالة وهي: القول بأن القرآن مخلوق. (2:7)

[2] Abu Bakr al-Khallāl (235 AH – 311 AH) was Abu Bakr Aḥmad ibn Muhammad ibn Harūn ibn Yazīd al-Baghdādi, known as al-Khallāl. He was a devout jurist, a distinguished scholar, and a renowned expert in ḥadīth among the Ḥanbali scholars. He compiled and arranged the jurisprudence of Imām Ahmad ibn Hanbal. He traveled to Persia, Sham, and al-Jazira seeking the jurisprudence, verdicts, and responses of Imām Ahmad ibn Hanbal.

[3] Hamād ibn ʿAbdullah ibn al-Mubārak, known as Abu Ja'far al-Qurashi, their freedman, al-Baghdādi, al-Mukhramī, al-Madani (173 AH – 254 AH), was a judge in Helwan. He was one of the leading scholars of ḥadīth, known for his reliability and preservation. Al-Dhahabi said: “The Imam, the distinguished scholar, the reliable guardian.”

[4] The Jahmiyyah, also known as the Jahmites, were a sect in early Islamic theology named after Jahm ibn Safwān, who lived in the 8th century CE. They held theological views that were considered deviant by mainstream Islamic scholars. Some of their beliefs included denying divine attributes, particularly those related to God's speech and actions, as well as rejecting predestination. They emphasised the use of reason and intellect in theological matters and were known for their extreme rationalism. The Jahmiyyah were opposed by prominent scholars of their time, such as Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal, who vigorously refuted their beliefs. Over time, the Jahmiyyah became marginalised, and their theological views were largely rejected within Sunni Islam. However, their influence can still be seen in certain philosophical and theological debates within Islamic thought.

[5] السنة للخلال روى الخلال عن المخرمي: «أنه قال لأبي عبد الله أحمد بن محمد بن حنبل: الواقفة؟ قال: هم شر من الجهمية، استتروا بالوقف» (۱٢٩/٥)، برقم (۱۷۸۲).

outcome of both positions is the same: denying the truth that the Qurān is the eternal word of Allāh and not created.

Qiwām al-Sunnah al-Asbahānī (d. 535 AH)[1] expounds on this matter, stating, “So, disapproving of it (al-munkar) is akin to having doubt (al-shakk), and doubt and denial (al-inkār) in it constitute disbelief (kufr). Consequently, the one disapproving of it (al-munkar) is deemed Jahmi, while the one in doubt is classified as al-wāqifi (those who do tawaqquf).” [2]

In summary, the improper use of tawaqquf can arise when there is a misrepresentation of its application to both word and meaning or when it is wielded to obscure consensus interpretations. This misapplication may inadvertently lead to the introduction of alternative interpretations that lack evidential support. Therefore, it is crucial to exercise caution and clarity when applying tawaqquf to avoid misrepresentation and misapplication in theological discourse. Theological tawaqquf is not a tool for unrestricted interpretations but must adhere to established linguistic and theological norms and respect consensus among scholars.

SECTION 2 – PRINCIPLES DETERMINING OBLIGATIONS AND BELIEFS

The Principles Related to the Obligation of the Consensus of Ahl al-Sunnah w’al-Jamāʿah regarding the Acceptance of Meanings of Words in Scripture

Interpretation of Clear, Explicit and Ambiguous Text in Creedal Matters

The Qurān and Ḥadīth contain both explicit and implicit meanings, leading to a nuanced understanding of their teachings. This intricate science warns against the dangers of misinterpretation and deviation, stressing the necessity of applying a systematic and correct methodology. Surah Āl Imrān addresses this diversity of clarity in Quranic verses, urging believers to guard against misinterpretation by those with ulterior motives. It underscores the significance of profound knowledge and understanding among sincere believers, while affirming that the ultimate interpretation rests with Allāhﷻ.

هُوَ الَّذِي أَنزَلَ عَلَيْكَ الْكِتَابَ مِنْهُ آيَاتٌ مُّحْكَمَاتٌ هُنَّ أُمُّ الْكِتَابِ وَأُخَرُ مُتَشَابِهَاتٌ ۖ فَأَمَّا الَّذِينَ فِي قُلُوبِهِمْ زَيْغٌ فَيَتَّبِعُونَ مَا تَشَابَهَ مِنْهُ ابْتِغَاءَ الْفِتْنَةِ وَابْتِغَاءَ تَأْوِيلِهِ ۗ وَمَا يَعْلَمُ تَأْوِيلَهُ إِلَّا اللَّهُ ۗ وَالرَّاسِخُونَ فِي الْعِلْمِ يَقُولُونَ آمَنَّا بِهِ كُلٌّ مِّنْ عِندِ رَبِّنَا ۗ وَمَا يَذَّكَّرُ إِلَّا أُولُو الْأَلْبَابِ

[1] Ismaʿīl ibn Muhammad ibn al-Faḍl ibn ʿAli al-Qurashi al-Talhi al-Taymi al-Asbahāni (d. 535 AH), known as Abū al-Qāsim, nicknamed “Qiwām al-Sunnah,” was one of the eminent preservers of knowledge. He was an authority in the fields of Quranic exegesis, ḥadīth, and linguistics, and he was one of the teachers of Imām al-Suyūti in ḥadīth.

[1] الحجة في بيان المحجة وشرح عقيدة أهل السُّنَّة، المؤلف: إسماعيل بن محمد بن الفضل بن علي القرشي الأصبهاني أبو القاسم، الملقب بقوام

السنة ، المحقق: محمد بن ربيع المدخلي ومحمد بن محمود أبو رحيم الناشر: دار الراية – السعودية – الرياض، الطبعة الثانية ١٤١٩ هـ – ١٩٩ م . يقول قوام السنة الأصبهاني الله في مسألة خلق القرآن : «فالمنكر فيه كالشاك، والشك والإنكار فيه كفر، فالمنكر الجهمي والشاك الواقفي» (۱/ ۲۳۸).

“It is He who has sent down to you, [O Muhammad], the Book; in it are verses [that are] decisive (al-muḥkam) – they are the foundation of the Book – and others ambiguous (al-mutashābih). As for those in whose hearts is deviation [from truth], they will follow that of it which is unspecific, seeking discord and seeking an interpretation [suitable to them]. And no one knows its [true] interpretation except Allāh ﷻ. But those firm in knowledge say, “We believe in it. All [of it] is from our Lord.” And no one will be reminded except those of understanding.” (Q. 3:7)

Scholars hold varied perspectives on the definitions of “al-muhkam” (clear expressions) and “al-mutashābih” (ambiguous expressions) within the Qurān. Upon scrutiny, these interpretations do not reveal discord but rather demonstrate similarities and convergences. Notably, the viewpoint of Imām Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī[1] (d. 606 AH) provides a particularly lucid and detailed explanation that aligns with the consensus of the majority. He stresses that the distinction between decisiveness and ambiguity lies in the clarity of the intended message conveyed by the speaker's words. Al-Rāzī's comprehensive elucidation addresses this crucial aspect, shedding light on nuances that scholars have approached differently in their definitions of “al-muḥkam” and “al-mutashābih.” According to Imam al-Razi, a prominent position adopted by many scholars, the terms “al-muḥkam” and “al-mutashābih” can be understood as follows:[2]

[1] Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (فخر الدين الرازي), Abū ʿAbdullah Muhammad ibn ʿUmar ibn al-Hasan ibn al-Husayn ibn Ali al-Rāzi, known as al-Tabrastāni al-Mawlid, al-Qurashi, al-Taymi, al-Bakri, al-Shāfiʿī, al-Ashʿarī, nicknamed Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī and Ibn Khattīb al-Ray, Sultan of the Logicians, the Shaykh of Reasoning, and the Transmitted. He was an imām, a commentator, a jurisprudent, and a scholar of fundamentals. His encyclopedic research and writings extended from humanities and linguistic sciences to pure sciences such as physics, mathematics, medicine, and astronomy. He was born in Rey, Qurashi by lineage, with origins from Tabaristan. He travelled to Khwarazm, Transoxiana, and Khorasan, where people were attracted to his books, which he taught, and he was proficient in the Persian language. He championed the Ashʿarī creed and was renowned for his rebuttals against philosophers and Muʿtazilites. He authored numerous beneficial works, including “al-Tafsīr al-Akbar,” which he called “Mafātīḥ al-Ghayb,” compiling what was not found in other commentaries, as well as “Al-Maḥṣūl fī ʿIlm al-Uṣūl” in the science of uṣūl, “al-Muṭālib alʿĀliyah” and “Ta’sīs al-Taqdīs” in theology and ʿilm al-kalām, as well as many more. He passed away in the city of Herat in the year 606 AH.

[2] في مناهل العرفان في علوم القرآن [الزرقاني، محمد عبد العظيم] أن المحكم ما كانت دلالته راجحة وهو النص والظاهر أما المتشابه فما كانت دلالته غير راجحة وهو المجمل والمؤول والمشكل ويعزى هذا الرأي إلى الإمام الرازي واختاره كثير من المحققين وقد بسطه الإمام فقال ما خلاصته.

اللفظ الذي جعل موضوعا لمعنى إما إلا يكون محتملا لغيره أو يكون محتملا لغيره الأول النص والثاني إما أن يكون احتماله لأحد المعاني راجحا ولغيره مرجوحا وإما أن يكون احتماله لهما بالسوية واللفظ بالنسبة للمعني الراجح يسمى ظاهرا بالنسبة للمعنى المرجوح يسمى مؤولا وبالنسبة للمعنيين المتساويين أو المعاني المتساوية يسمى مشتركا وبالنسبة لأحدهما على التعيين يسمى مجملا وقد يسمى اللفظ مشكلا إذا كان معناه الراجح باطلا ومعناه المرجوح حقا.

إذا عرفت هذا فالمحكم ما كان دلالته راجحة وهو النص والظاهر لاشتراكهما في حصول الترجيح إلا أن النص راجح مانع من الغير والظاهر راجح غير مانع منه.

أما التشابه فهو ما كانت دلالته غير راجحة وهو المجمل والمؤول والمشكل لاشتراكها في أن دلالة كل منها غير راجحة وأما المشترك فإن أريد منه كل معانيه فهو من قبيل الظاهر وإن أريد بعضها على التعيين فهو مجمل.

ثم إن صرف اللفظ عن المعنى الراجح إلى المعنى المرجوح لا بد فيه من دليل منفصل وذلك الدليل المنفصل إما أن يكون لفظيا وإما أن يكون عقليا والدليل اللفظي لا يكون قطعيا لأنه موقوف على نقل اللغات ونقل وجوه النحو والتصريف وموقوف على عدم الاشتراك وعدم المجاز وعدم الإضمار وعدم التخصيص وعدم المعارض العقلي والنقلي وكل ذلك مظنون والموقوف على المظنون مظنون.

وعلى ذلك فلا يمكن صرف اللفظ عن معناه الراجح إلى معنى مرجوح بدليل لفظي في المسائل الأصولية الاعتقادية ولا يجوز صرفه إلا بواسطة قيام الدليل القطعي العقلي على أن المعنى الراجح محال عقلا وإذا عرف المكلف أنه ليس مراد الله تعالى فعند ذلك لا يحتاج إلى أن يعرف أن ذلك المرجوح ما هو لأن طريقه إلى تعيينه إنما يكون بترجيح مجاز على مجاز وبترجيح تأويل على تأويل وذلك الترجيح لا يكون إلا بالدلائل اللفظية وهي لا تفيد إلا الظن والتعويل عليها في المسائل القطعية لا يفيد لذا كان مذهب السلف عدم الخوض في تعيين التأويل في المتشابه بعد اعتقاد أن ظاهر اللفظ محال لقيام الأدلة العقلية القطعية على ذلك اهـ (2:274)

Al-muḥkam (the clear) refers to text with decisive indications, such as the explicit text “al-nass” (clear expression), primarily due to their shared tendency to establish predominance. However, while the explicit text is predominant and exclusive, the apparent interpretation is predominant yet not exclusive.

Al-mutashābih (the ambiguous) refers to text with indications that lack decisiveness, encompassing meanings such as ‘al-mujmal' (unclear), ‘al-mu’awwal' (diverted expression), and ‘al-mushkil' (problematic expression) due to their shared characteristic of having non-decisive indications. Regarding Al-mushtarak (the homonym), if all its meanings are intended, it falls under ‘al-ẓāhir' (the apparent), but if only some meanings are intended, it is categorized as ‘al-mujmal.'

The term designated to convey meaning either exclusively signifies one interpretation or potentially signifies multiple interpretations. The former denotes “naṣṣ” (clear expression), while the latter scenario can either emphasize one interpretation over another, rendering it predominant for one meaning and dubious for another, or it can equally apply to both interpretations. In the context of emphasizing the predominant interpretation, it is termed “al-ẓāhir” (apparent), whereas in reference to the dubious interpretation, it is termed “al-mu’awwal” (diverted expression). When the meaning has no predominant interpretation and the word equally encompasses two interpretations, it is termed “al-mushtarak” (Homonym). If assigned to a specific interpretation only and not to multiple, it is termed “al-mujmal” (unclear), and if its predominant interpretation proves false while the dubious interpretation holds true, it may be labelled “al-mushkil” (problematic expression).

When a word's meaning is diverted from its predominant (al-rājiḥ) interpretation to a dubious (al-marjūḥ') one, separate evidence (al-dalīl al-munfaṣil) is required, which can be linguistic or rational. Linguistic evidence, however, is inconclusive as it relies on language transmission, grammatical rules, and conjectural knowledge, which is itself based on conjecture (‘maẓnūn‘). Consequently, linguistic evidence cannot definitively alter a word's meaning from its predominant one to a dubious one in matters of creedal fundamentals.

Such alteration is permissible only with the establishment of conclusive rational evidence proving the logical impossibility of the predominant meaning.

If the accountable person discerns that Allāhﷻ does not intend a particular interpretation, then there's no necessity for them to ascertain the specific dubious meaning, as its determination relies solely on a preference for metaphor (al-majāz) over metaphor and interpretation (al-ta’wīl) over interpretation. Such preference can only be established through linguistic evidence, which inherently implies conjecture (ẓann).

Relying solely on linguistic evidence in matters of ultimate significance is deemed invalid. Therefore, the practice of the predecessors was to abstain from delving into the interpretation of the ambiguous (mutashābih) once they believed that the apparent meaning of the word was impossible, supported by conclusive rational evidence. In such cases, they adopted a position of non-commitment (al-tawaqquf), recognizing that such meanings are ultimately unknowable.

Consensual Implication on Non-Explicit Wording

It is argued that when scripture remains silent on a particular issue, such as Adamic exceptionalism, a stance of tawaqquf should be adopted.[1] However, this argument overlooks a crucial aspect: while scripture may not explicitly address every nuanced topic, the consensus, ijmāʿ, of scholars can effectively restrict the interpretation of certain words or statements to a singular predominant meaning. In essence, this consensus establishes a definitive theological belief based on unanimous agreement and to oppose this is tantamount to innovation in belief, bidʿa.

As previously mentioned, this scenario can typically arise when the implication of a statement is widely understood and accepted, even though it may not be explicitly stated in scripture. In such cases, the indication is grasped through consensual implication rather than explicit wording, a concept known as dalātahu ʿalayhā mafhūman lā manṭūqan.[2] This concept is particularly relevant to unclear or ambiguous wordings (al-mutashābihāt) in scripture, which are given definitive contextual meanings affirmed through the ijmāʿ, consensus, of scholars. To interpret them solely through reason is incorrect as the intellect is not an independent source; rather, it requires the guidance of the divine law and direction towards proof. Relying solely on pure reason or pure science leads to divergence and

[1] Malik, S.A. Islam and Evolution, Al-Ghazālī and the Modern Evolutionary Paradigm, Routledge, London 2021, 134

[2] معارج القبول.واستدرك العلامة حافظ الحكمي الله على دلالته الصريحة فقال :«وقال النسائي : باب زيادة الإيمان ذكر فيه حديث الشفاعة، ودلالته منطوقاً على تفاضل أهل الإيمان فيه، وأما الزيادة والنقص فدلالته عليها مفهوماً لا منطوقاً (۳/ ۱۱۷۸)

وكذلك حديث : «نافق حنظلة» يدل على نقصان الإيمان وإن لم يصرح بلفظ النقص . أخرجه مسلم (٢١٠٦/٤)، برقم (٢٧٥٠).

dispute, for the intellect will not be guided except by revelation, and revelation does not negate sound reason.[1]

Prominent scholars emphasise the paramount importance of adhering to the Qurān, the Sunnah (the practices and traditions of the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him), and the consensus of scholars (Ijmāʿ) as the primary sources of guidance in Islamic jurisprudence and beliefs. They assert that those who adhere to these sources are considered part of Ahl al-Sunnah wa al-Jamāʿah, the mainstream of Islamic tradition. Moreover, they regard the companions of the Prophet Muhammad, may Allāh ﷻ be pleased with them all, as the foundational authority upon which the consensus and the correct understanding of the religion are built. Any deviation from these sources or innovation in religious matters is warned against, as it is considered a deviation from the path of guidance, with potential consequences in the Hereafter.[2]

In theological interpretations of Quranic verses where the meaning is not explicitly stated, several key principles guide the consensus of Ahl al-Sunnah wa al-Jamāʿah, particularly concerning implicit meanings derived from these verses related to theological positions. A firm theological stance can be deduced from non-explicit texts in the Sharīʿah sources or scripture based on the consensus of early generations and the scholarly opinions of recognized authorities from the past. These principles ensure a cohesive and tradition-based approach to understanding the Quran and its theological implications within the framework of Ahl al-Sunnah wa al-Jamāʿah, safeguarding the integrity and continuity of Islamic beliefs and practices.

The consensus of the salaf, the revered early generations of Muslims, stands as a cornerstone in Islamic scholarship. This consensus, comprising scholars from diverse backgrounds and fields of expertise, serves as a foundational pillar for theological understanding and interpretation. While it's acknowledged that differences in interpretation may emerge among later scholars, it is imperative to prioritize the consensus of the early generations as the bedrock of theological discourse.

Ibn Taymiyyah states; “The consensus (ijmāʿ) is something agreed upon by the majority of Muslims among the jurists, Sufis, scholars of hadith, theologians, and others as a whole. It has been acknowledged by most, but some of the people of innovation (ahl al-bidʿa) among the Muʿtazilites and Shīʿī have denied it. However, what is known is the consensus of the companions of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). As for what came after them, it is often difficult to establish with certainty, and that is why scholars have differed regarding

[1]الموسوعة العقدية [مجموعة من المؤلفين] المبحث الثالث: العقل الصريح] العقل مصدر من مصادر المعرفة الدينية، إلا أنه ليس مصدرا مستقلا؛ بل يحتاج إلى تنبيه الشرع، وإرشاده إلى الأدلة؛ لأن الاعتماد على محض العقل، سبيل للتفرق والتنازع ((إيثار الحق على الخلق)) لابن الوزير (ص ١٣))، فالعقل لن يهتدي إلا بالوحي، والوحي لا يلغي العقل (1:63)

[2] مجموع الفتاوى. ويقول شيخ الإسلام ابن تيمية -فمن قال بالكتاب والسنة والإجماع فهو من أهل السنة والجماعة (٣٤٦/٣)

شرح السنة – ويقول الإمام البربهاري -والأساس الذي تُبنى عليه الجماعة هم أصحاب محمد صلى الله عليه وسلم ورحمهم الله أجمعين، وهم أهل السنة والجماعة فمن لم يأخذ عنهم فقد ضل وابتدع وكل بدعة ضلالة والضلالة وأهلها في النار . .( ص ٦٧ )

what is mentioned about post-companion consensus (ijmāʿ) and have disagreed on certain issues, such as the consensus of the tābiʿūn (the generation after the companions) on one of the opinions of the companions, the consensus that did not disappear during the era of its people but was later disputed by some, silent consensus (ijmāʿ sukūti), and other forms of consensus”.[1]

The hierarchy within Islamic scholarship places the religious verdicts of the Companions of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) at the forefront, followed by those of the Successors (tābiʿīn), and subsequently, their followers (tābi' al-tābiʿīn), and so forth. This hierarchy reflects the principle that the closer an era is to the time of the Prophet, the more reliable and accurate its knowledge and interpretations are considered to be, especially concerning general principles rather than isolated cases. The disparity in knowledge and virtue between the early generations and later ones is likened to the distinction in faith and excellence between them.[2]

In navigating the ambiguity present in Quranic verses, the stance of Ahl al-Sunnah wa al-Jamāʿah underscores the reliance on scholarly opinions originating from the early generations. This reliance ensures that theological interpretations remain firmly rooted in the traditions and teachings of the Prophet Muhammad and his companions, who are regarded as the most credible authorities on matters of faith. It is widely recognized, among those who reflect upon the Qurān and Sunnah, and the consensus of the Sunni community, that the earliest generations of Muslims are unparalleled in their virtues, actions, beliefs, and all aspects of righteousness. The Prophet Muhammad himself affirmed the superiority of the early generations without dispute. They are revered for their comprehensive excellence, encompassing knowledge, deeds, faith, intellect, religion, eloquence, worship, and their adeptness in elucidating any ambiguities. Only those who obstinately oppose the established knowledge within Islam, and those who have been led astray by ignorance, would contest this undisputed truth. [3]

Even if a particular theological interpretation is not explicitly outlined in the Qurān, its acceptance based on the consensus of the salaf or those who adhere to their traditions through logical deduction carries immense significance. This consensus holds weight, even in

[1] مجموع الفتاوى [ابن تيمية] الإجماع وهو متفق عليه بين عامة المسلمين من الفقهاء والصوفية وأهل الحديث والكلام وغيرهم في الجملة وأنكره بعض أهل البدع من المعتزلة والشيعة لكن المعلوم منه هو ما كان عليه الصحابة وأما ما بعد ذلك فتعذر العلم به غالبا ولهذا اختلف أهل العلم فيما يذكر من الإجماعات الحادثة بعد الصحابة واختلف في مسائل منه كإجماع التابعين على أحد قولي الصحابة والإجماع الذي لم ينقرض عصر أهله حتى خالفهم بعضهم والإجماع السكوتي وغير ذلك (١١:٣٤١)